Get for FREE

Introduction

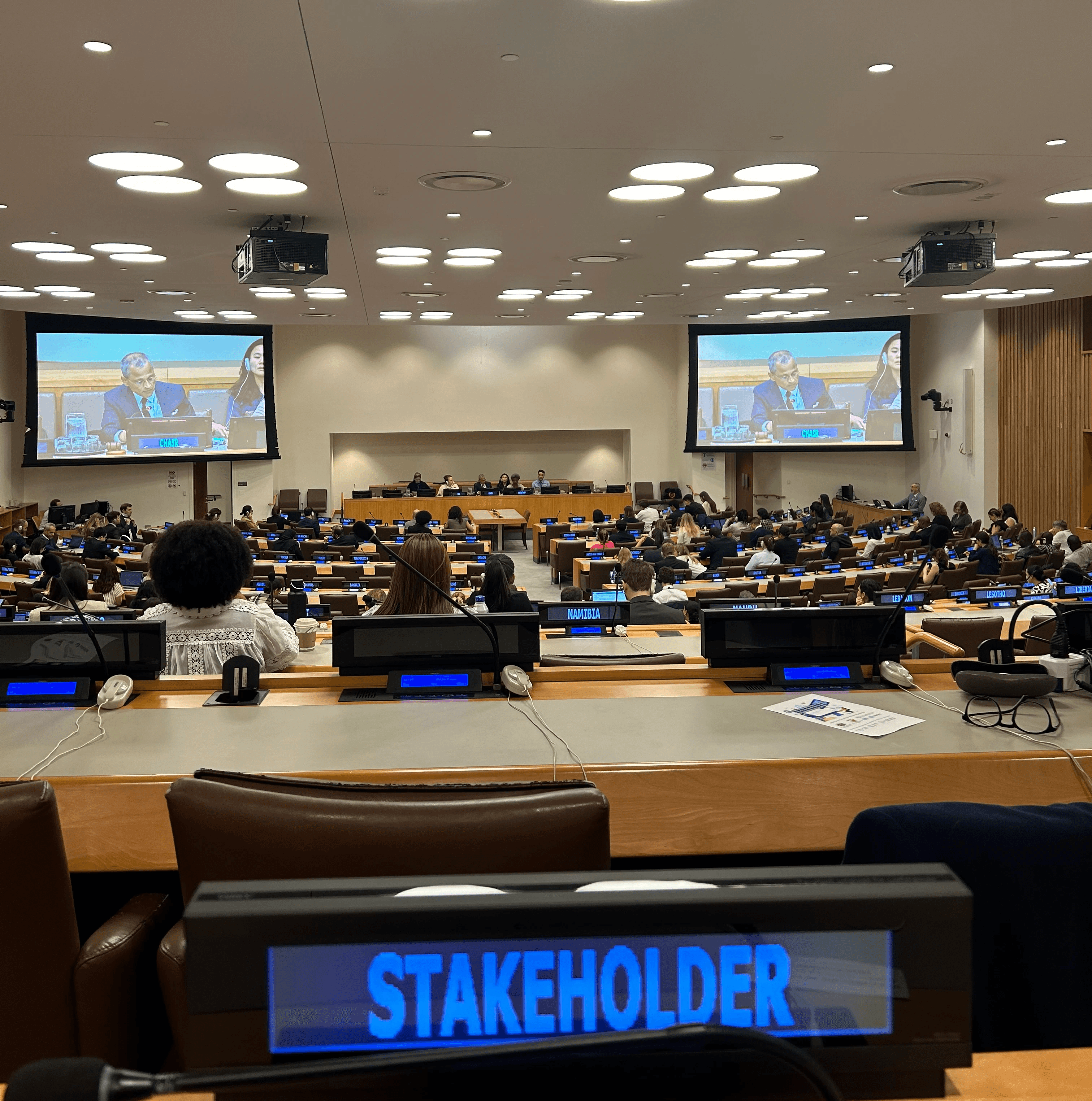

I had the privilege to attend the United Nations’ Open Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Cybersecurity and Information & Communication Technologies (ICTs) event between July 8th and 12th, 2024. It was the eighth substantive session out of eleven that are set to occur between June 2021 and July 2025 and are intended to assemble United Nations (UN) member states to discuss and confer the most pressing cybersecurity issues states are currently facing, as well as the future of international law in governing cyberspace. This week, I had the privilege of observing diplomats, experts, and representatives from various countries negotiate parts of the third Annual Progress Report (APR), which was published at the end of July. The first APR, released in July 2022, identified key threats and established foundational norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace. The second APR expanded this dialogue by refining these norms and delving into implementation and confidence-building measures. The third APR was significant not only for building on the groundwork laid by its predecessors but also for introducing concrete steps toward capacity-building, international cooperation, and accountability.

This year’s APR highlighted the OEWG Chair’s proposal for a Voluntary Checklist of Practical Actions, aimed at implementing voluntary, non-binding norms of responsible state behavior. Additionally, the third APR addressed new topics, including AI security concerns, such as the protection of data used in machine learning and AI models, and provided a more detailed examination of ransomware and crypto theft threats. It also introduced the Global Points of Contact (POC) directory, launched in May 2024, which includes authorized individuals and organizations involved in international cybersecurity. This directory is a key confidence-building measure, facilitating open communication and fostering a collaborative environment where nations are more likely to share information and work together.

I will now cover the biggest takeaways/themes of the event.

Long-awaited acknowledgment of crypto threats

One of the most significant takeaways from the eighth substantive session I noted was the overdue discussion of cryptocurrency-related threats. During the session, I saw delegates from South Korea, Japan, and the US raise concerns about the theft of crypto and its implications for international peace and security. In the final published draft of the event's proceedings, there was a pivotal acknowledgment of the growing threat that cryptocurrencies pose in cyberspace: "States also highlighted with concern rising cryptocurrency theft and financing of malicious ICT activity using cryptocurrency which could potentially impact international security." (p. 4 para. 20).

This development is particularly meaningful to me, as my senior thesis focused on the cybersecurity implications of cryptocurrencies, especially in the context of ransomware and other malicious software. One of my primary frustrations during my senior year was the lack of attention given to crypto and other emerging technologies, in both academic circles and policy/diplomacy circles. For instance, I attended the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) flagship Cyber Stability Conference in March 2023, hoping to observe fruitful discussions on cybersecurity in cryptocurrencies, but there was no mention of digital assets. Despite the clear dangers in light of attacks from both non-state and state actors alike, particularly Advanced Persistent Threats, there seemed to be a reluctance to address these issues comprehensively.

Seeing crypto threats explicitly mentioned and discussed at such a high-profile international forum validated the concerns I raised in my thesis and reinforced the importance of ongoing research and dialogue in this area. It signaled a shift in the global cybersecurity discourse, indicating that policymakers and international bodies have begun to broadly recognize that these are not just niche issues but central to international security. However, this development also underscores the slow, deliberate nature of diplomatic processes according to the pace of norms creation. The first recorded

The evolving nature of cryptocurrency threats demands that we stay ahead of the curve, ensuring that our frameworks and responses are adaptable and proactive.

2) A clear emphasis on precision

Diplomacy is as much about precision as it is about persuasion and negotiation.

One of the most surprising and eye-opening aspects of the UN OEWG session was witnessing firsthand how meticulous and detail-oriented delegates and ambassadors were throughout the APR drafting process. The technical precision in their negotiations was striking. For instance, China advocated for a seemingly minor yet significant change in a phrase from "key function" to "one of the key functions," highlighting their focus on specific wording. This reminded me that even the smallest linguistic adjustments can have important implications in shaping international agreements. Each clause, term, and phrase, represents broader state and multilateral considerations. Being an observer to these rigorous debates deepened my understanding of the complexities that are inherent in international lawmaking, in which the nuances of language can become battlegrounds for competing ideologies and political strategies.

The meticulous nature of these negotiations is a testament to the high stakes involved and the commitment of states to shape a safer, more stable international environment. As more states engage in cyber activities with potential military implications, it becomes increasingly evident that agreeing on norms is not easily attainable, and that the road to codifying hard law in cyberspace is a long one.

3) Applicability of International Humanitarian Law

A particularly intense debate centered around the applicability of international humanitarian law (IHL) to cybersecurity. This topic was hotly contested, especially by states like Russia, China, and Iran. Countries like the US, Japan, Austria, Switzerland, and France advocated strongly for the inclusion of IHL, arguing that it serves as a useful framework for protecting civilians and maintaining order during cyber conflicts. Ultimately, the reference to IHL was left out of the final document because it proved too contentious. From my perspective, the inclusion of IHL in state discussions on cyberspace is crucial, particularly in a rapidly digitizing world where not only companies, individuals, and militaries operate on a shared digital landscape that transcends national borders, but also blurs the lines between civilian and military activities. In this interconnected environment, there is great potential for cyber operations to cause unintended harm to civilian infrastructure—such as power grids, healthcare systems, and communication networks. International humanitarian law (IHL) provides essential protections for civilians during times of peace and times of conflict by regulating the use of force in cyberspace, offering recourse and parameters for acceptable state behavior, and establishing principles of proportionality and necessity. Without IHL, we lack the guided behaviors for what is lawful during times of peace and war, potentially leading to unchecked brute force.

However, the reality of implementing IHL into global cyber frameworks is much more complicated. Many experts and certain states have argued that including IHL in discussions about cyberspace legitimizes or encourages conflict by implying that cyberspace is an accepted domain for military operations. While a majority of observers do not see a direct link between recognizing IHL applicability and the militarization of cyberspace, this concern, primarily voiced by China, posits that citing the jus in bello body of law in cyberspace discussions could inadvertently militarize the domain, thereby giving legitimizing inappropriate invocations of IHL to a given state’s strategic plans.

Such arguments track back to a history of stalled international law discussions in various Group of Governmental Experts (GGEs) meetings. For years, states have found disagreement over the role of international humanitarian law in cyberspace discussions.

4) Geopolitical clashes over International Law

This leads me to a fourth big takeaway - underlying these technical debates are larger geopolitical tensions that harken back to the early days of global cyber negotiations, and were evidently reflective of a general trend of pushback against Western dominance. IHL is a tool of the current legal order under the Western, US-sanctioned international legal order, and I witnessed Russian delegates and Chinese delegates pushing for arguments against the mention of IHL in the APR.

Historically, the Russian Federation has proposed an alternate regime of cyber conduct, called the Code of Conduct on Information Security as early as 1998, calling for a special UN instrument to bolster information security. This proposal, with updates, was repeated by China and Russia in 2011 and again by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation in 2015. The 2015 proposal included a recommendation to change the current Internet governance model, giving governments more control instead of the multistakeholder community. Western governments opposed this, fearing it would legitimize censorship by authoritarian regimes and facilitate further content control. This resistance has been a recurring theme in UN First Committee discussions, contributing to failures to reach consensus in the UN GGE meeting in 2011?.

This leads to the present-day, where now, there exists a bloc of states, led by the Sino-Russian camp and including Iraq, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Belarus, and Cuba, that push back against the current international legal order in cyberspace. They argue that cyber norms alone are insufficient and propose a new legally binding instrument on international cybersecurity. In contrast, the US, UK, Australia, Japan, France, Germany, Netherlands, and allied states, along with developing countries like Brazil, Argentina, Costa Rica, South Africa, and Kenya, advocate for focusing on implementing previously agreed cyber norms rather than revisiting foundational principles.

The reluctance of some states to embrace IHL in the context of cyberspace is not just about legal principles but also about power dynamics and strategic interests. The OEWG session illuminated how deeply these historical and geopolitical tensions are embedded in current negotiations, underscoring the complex interplay of legal, strategic, and political factors shaping the future of international cybersecurity law.

It was interesting that despite an overwhelming number of Western states including the US, Argentina, Switzerland, Austria, Japan, and France that expressed remorse over the exclusion of IHL from the final APR report, the Sino-Russia bloc got their way. I think this reflects the broader state of geopolitical balance, where because of all the historical disagreement, Western countries knew they had to concede on that point to achieve majority consensus. To not achieve consensus on a soft-law reporting structure, not even a hard-binding legal form like a treaty, would have bred loss of confidence in the cyber discussions and progress of state cooperation and coordination.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the report was passed with total consensus on July 13th, 2024.

Looking ahead, the outcome of cyber negotiations will likely hinge on the broader geopolitical climate among major players. The deteriorating relations between the US, China, and Russia underscore this dynamic. As these tensions escalate, they will inevitably impact the effectiveness and direction of cyber diplomacy. In the realm of international law, the concepts of jus ad bellum (the right to go to war) and jus in bello (the right conduct within war) are central. Traditionally, warfare has been framed around kinetic effects—physical damage and military engagements. However, cyber warfare challenges these conventions. The distinction between a cyber attack and a conventional conflict is increasingly blurred, raising questions about how existing legal frameworks apply to digital confrontations.

Future discussions will need to address this evolving landscape, especially as cyber operations become more integrated into national security strategies. Understanding how to balance traditional notions of conflict with the realities of cyber threats will be crucial. I look forward to seeing how these debates will continue to unfold, particularly how we define and regulate the intersection of cyber operations and conventional warfare.